“It is often said that behind every great man is a great woman”. This is the pitch by the National Party Botany electorate branch to attend their “Ladies Afternoon Tea with Amanda Luxon”. For $110 including GST, you can turn up on Saturday 20 April to meet the Prime Minister’s wife “in a relaxed setting to hear her journey into the political realm at Christopher’s side”. The advertisement promises “afternoon tea and bubbles in a beautiful private garden setting in the electorate of Botany.”

It's not unusual for political parties to fundraise like this. And some functions to meet with influential political figures charge much more. In 2019, Labour’s fee for lunch with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern was $1500, then rising to over $2000 in 2021.

Although meeting with Amanda Luxon might not be the same as lunching with the actual PM, there’s no doubt that she is strongly influential on Luxon himself. Yesterday the Herald’s Audrey Young listed her, unsurprisingly, as one of his closest influences and advisers – see: Christopher Luxon’s inner circle – the Prime Minister’s most important advisers (paywalled)

How much the parties spent on advertising in last year’s election

This mix of money and political influence is highlighted by the Electoral Commission’s release yesterday of last year’s election expenses of the political parties. All the parties competing in the 2023 election were required to declare their total spending on advertising for the three-month-period before election day. You can see all the figures here: Party expenses for the 2023 General Election

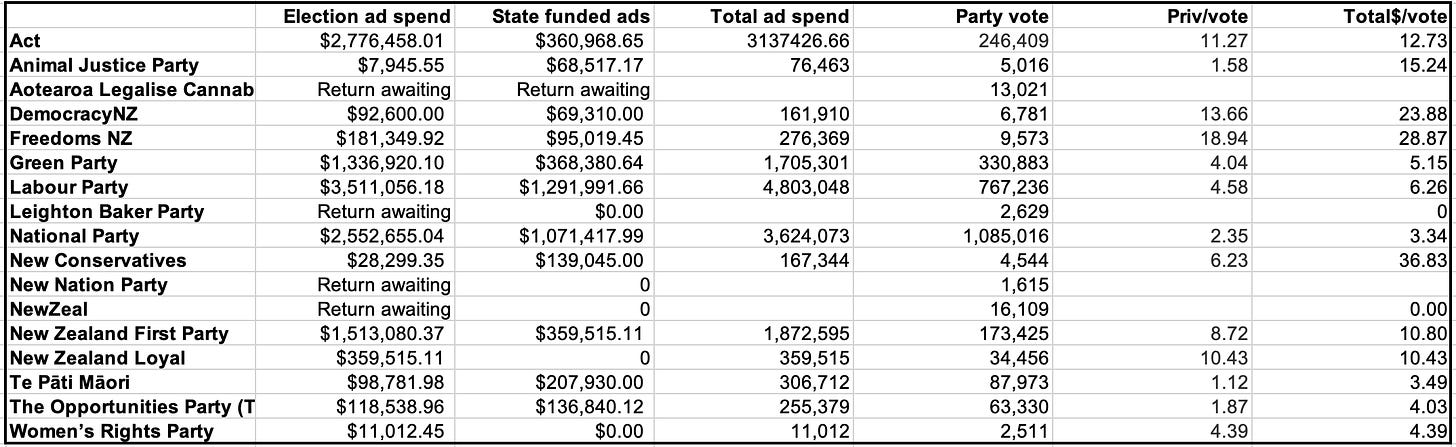

Below is a table of the expenditure, showing how much was spent by each party, with details of their state-funded election advertising as well, and how much this worked out in terms of value for money compared with their party vote.

The Labour Party was easily the biggest spender – paying $4,803,048 for advertising, including its $360,968 of advertising spend allocated by Electoral Commission. Labour therefore spent $6.26 for each party vote it won (or only $4.58 if you want to disregard the taxpayer-funded ads).

The second biggest spender, National, was about $1.2m behind Labour. Altogether the party spent $3,624,073, or $3.34 per vote, meaning they achieved a very good “bang for their buck”.

Act spent $3,137,427 in total on advertising, making it the third biggest spending. But because they got much fewer party votes, they had the highest cost per vote of those that made it into Parliament – $12.73.

The fourth biggest spender was NZ First, with a total spend of $1,872,595, producing a relatively high cost of $10.80 per vote.

The Greens, in fifth place, got much better value for their advertising spend of $1,705,301 – $5.15 per vote.

Te Pāti Māori was a distant sixth place out of the parties that got into Parliament. They only spent $306,712, of which two-thirds was their state-funded allocation for advertising. Their lower spend meant that they achieved the best value per vote of those in Parliament – only $3.49.

Of the parties outside of Parliament, TOP managed $4.03 per vote, DemocracyNZ $23.88 per vote, and Freedoms NZ: $28.87 per vote.

How the parties spent their advertising money

The declarations of advertising spending by the parties must include details of how the money was spent. Herald political editor Claire Trevett has delved into these details, and highlights that the National Party spent “$319,000 for ad production and ‘tactical ads’ on social media platforms” via its campaign social media team, Topham Guerin – see: Act Party’s election-spending bid to block NZ First - and how Labour outspent National

As Trevett explains, “Topham Guerin has done social media for campaigns for conservative parties such as National, Australia’s Liberals and the UK Conservatives, including former Prime Minister Boris Johnson.”

Trevett also draws attention to the interesting “disparity in overall election spending” by which Labour outspent National on advertising “despite National far outstripping Labour in securing donations leading up to the election. Between 2021 and the 2023 election, Labour had declared $1.3m in donations while National declared about $9m.” But of course, parties spend their campaign budgets on all sorts of expenses aside from paid advertising, and Trevett says “Parties do not have to disclose their spending on party and campaign staff, or such things as polling.”

Hence, it needs to be remembered that the election spending figures are only for advertising, and they are only for the three months leading up to election day, even though we now have something of a “permanent campaign” in which parties are effectively spending on electioneering throughout the parliamentary term.

The spending on Act’s election attack ads against Winston Peters are also detailed by Trevett. During the campaign last year, Act launched digital ads and billboards with the words “Don’t be Fooled Again”, showing Peters’ face. Trevett reports: “Act’s return lists how much it spent on attack ads in an attempt to keep NZ First out of Parliament – Act’s return includes a $100,000 expense in August for advertising that related to Winston Peters from a digital advertising company, as well as some smaller bills for other material that was related to Peters.

The Post’s Thomas Manch has also looked at the party’s various advertising spends say about the campaigns the party’s ran last year. For example: “Labour ran a broad-spectrum campaign, spending $115,300 on posting mailers, more than $170,000 on Facebook adverts, some $141,000 for corflute hoardings, and $143,870 on one high-end event production firm” – see: Labour spent $1m more than National to lose the 2023 election (paywalled)

Labour’s hiring of individual professionals ranged, according to Manch, from paying actor Tammy Davis “$74,750 to voice Labour Party adverts”, through to $575 for entertainer Anita Wigl’it to help launch the party’s Rainbow strategy.

The article also explains that NZ First spent a combination of money on digital billboards ($172,500) and lots on local community newspapers. The Greens in contrast directed money towards TVNZ ($100,000), YouTube ($50,000), and Phantom Billstickers to put up paper posters (deemed better than using too many environmentally-unfriendly plastic corflute hoardings).

Electorate candidate spending

The details above are all about how the political parties spent money on trying to win the all-important party vote. But decent amounts of money were also spent by local electorate candidates at last year’s election.

The National Party candidates tended to be the biggest spenders, and interestingly a lot of the money that they declared recently in donations came from the National Party headquarters. Hence, although Labour spent a lot more than National in advertising for the party vote, National directed a lot of its money to its candidates to try to win individual seats.

This was all covered very well last week by RNZ journalist Farah Hancock in her article: How electorate candidates funded their campaigns - and who spent the most

Here is her most interesting findings: “The National Party poured money into winning electorate seats, donating almost $2 million from its own coffers to its candidates. An RNZ analysis of data released by the Electoral Commission shows National donated more money to its own candidates than candidates from all other parties combined received from all sources ($1.4m). Eighty percent of money received by National Party candidates came from party affiliated coffers and 9 percent came from businesses or individuals.”

Of course, Labour also donates money to its candidates, and Hancock found that nearly 50 per cent of donations to Labour candidates came from the party.

Hancock also looked at the big spending figures in the campaign. The biggest spender was Scotty Bright of the DemocracyNZ party – he apparently spent $42,000 in his unsuccessful campaign to win Port Waikato. Although curiously, this is well over the legal limit of $32,600 imposed on candidates.

The second biggest spender was Labour’s Rachel Boyak who won Nelson by a margin of just 26 votes, spending $32,561, just under the legal limit. The third biggest spender was Julie Anne Genter ($32,555) for her successful Green campaign in Rongotai. Close behind her was TOP’s Raf Manji who ran unsuccessfully in Ilam.

Also, of interest in this RNZ piece, NZ First MP Tanya Unkovoch “spent the most per vote gained. Unkovich stood in Auckland's Epsom electorate and spent $11,344, receiving 573 votes.” And in the Northland electorate, the candidates together spent over $100,000 – making it the most expensive race in the country.

Overall, we can see some huge differences in spending by New Zealand politicians trying to win the public’s vote. And if you “follow the money”, you can often detect where influence lies. But not all money spent in politics is very efficient – hence the way politicians spend their money doesn’t directly translate into power. The fact that the Labour Party was able to spend so much but lose so disastrously in 2023 provides a lesson in how money in politics is often more complicated than many people assume.

Dr Bryce Edwards

Political Analyst in Residence, Director of the Democracy Project, School of Government, Victoria University of Wellington

This article can be republished for free under a Creative Commons copyright-free license. Attributions should include a link to the Democracy Project (https://democracyproject.nz)

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/sir-john-keys-former-parnell-home-resale-of-mansion-loses-7m/KKM7NBNTFVDHBMRPEB37I6CL64/#:~:text=Ben%20Leahy&text=A%20Chinese%20businessman's%20decision%20to,years%2C%20according%20to%20new%20data.

Draw your own conclusion

I wonder if there’s a meaningful way to factor in the oft mentioned “protest vote”. Act in 2020 when the National leadership was a shambles, and potentially the Greens this last election given Labour’s woes. I suppose it’s impossible. Not enough data. Too vague a premise. But it sure would be interesting to think about “cost of acquiring a non-party faithful”, cost of “flipping a blue to red (etc.)”, cost of maintaining party loyal vote, cost of preventing defection within one’s own block (left/right). Especially with the Greens wanting to be the premiere left wing party, it’ll be all the more important.